Conflicts have dominated the relationship between Germans and Danes in the border region for more than a century. However, in spite of – or maybe even because of – the turbulent relationship, Hinrich Jürgensen, President of the German minority in Denmark, believes the two people today not only accept each other, but desire one another.

By Stine Skovgaard

Hinrich Jürgensen lives in Southern Jutland. Or in Northern Schleswig. Sight lies in the eyes of the beholder. Affiliation and national identity has characterized the border area between Germany and Denmark for as long as anyone can remember. His father was convicted for treatery after World War II and as a child, he experienced name calling like “Hitler swine”.

“In Tingleff we had double of everything – two schools, two sport halls and so on. We were pretty good at handball at our school. However, when we were out to play handball there was often a conflict – not so much on the court, but the parents standing on the side of the court would yield “German swine” at us kids,” Jürgensen recalls.

The referendum in 1920 following the end of World War I forced the people in the area to pick a side and the new dividing line left national minorities behind on each side of the border. As his last name reveals, Jürgensen’s family belongs to the German minded Schleswigere, who were left on Danish territory. The two World Wars and the demarcation have left deep scars in the relationship and still impacts generations as we celebrate the 75th anniversary for WWII’s end and the 100th anniversary for the reunification of South Jutland and Denmark.

Hinrich Jürgensen is President for Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger, an umbrella organization for the German minority and their activities in Denmark. However, he first and foremost consider himself a South Jutlander:

“My family has always been South Jutlanders or Schleswigers but with German culture. My mother tongue is South Jutlandic,” he explains in a heavy dialect.

The 1920 border made many German minded families Danes, however, they insisted on keeping their culture and traditions. As Hitler gained power, the German minority saw how the Germans reconquered lost domains, which fueled their patriotism. A strong nazification started to dominate the minority.

“The German-minded did not accept the demarcation of 1920. It is legitimate for a minority to wish for a border alteration,” Jürgensen says. “I believe the minority wanted to show Hitler that they were just as German as before the border was moved. Especially the political top of the minority propagandized to get the youth to volunteer.”

Left as heroes, returned as traitors

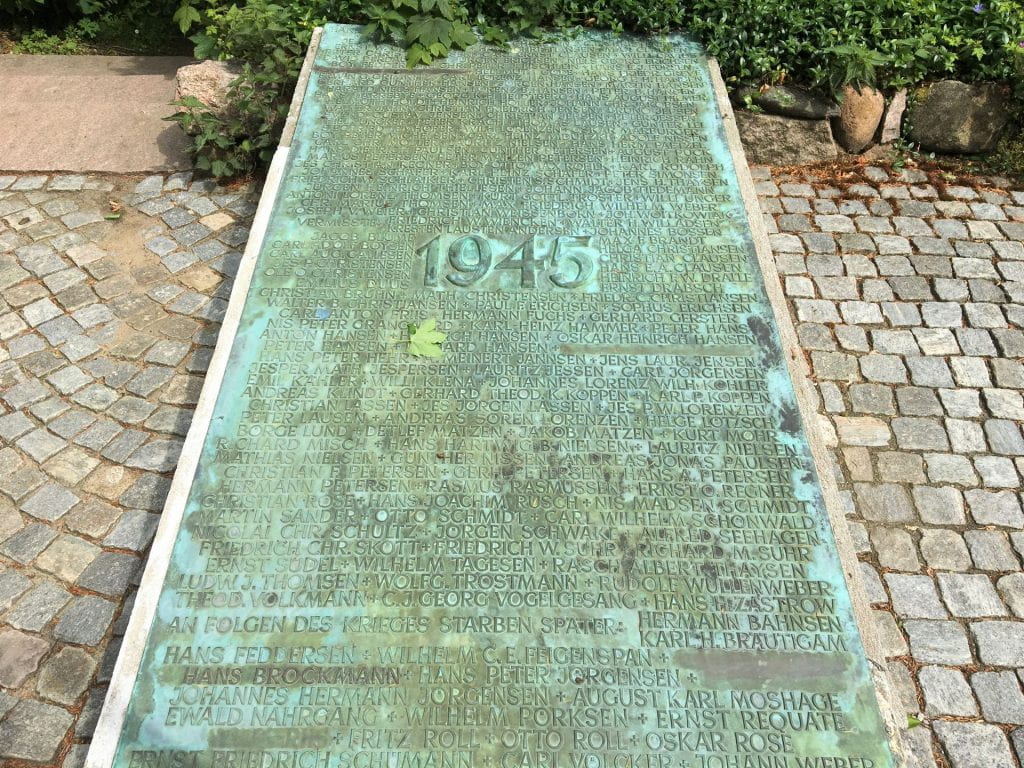

As Denmark was occupied by Germany, the Nazis recruited volunteers for the army on Danish territory, and the patriotic minority was a relatively easy target. More than 2100 people from the minority served at the German front line.

Many of those who did not volunteer for front service became Zeitfreiwillig – local defense volunteers. Together with around 1600 German minded South Jutlanders, Hinrich’s father, Nis Friedrich Jürgensen, wore a German uniform at the weekly meetings as well as participated in armed military practice.

As Germany surrendered in 1945, the young volunteers returned to South Jutland, defeated and with no hope for a reunification with the homeland. Danes, who’s land had been occupied for five years and who’s people had been detained or deported now lived side by side with men who had turned their back to Denmark, had worn a German uniform and fought for Hitler. South Jutland was a ticking bomb.

Denmark legislated retrospectively to convict those, who had fought for foreign power. More than 3000 members of the German minority were detained equaling to every fourth man of the minority, and many of them later prosecuted with treatery or foreign military service.

“The minority considered themselves victims for a long time. It was not them, who had done anything wrong. It was Hitler who had seduced them and thereby they lost young men fighting his war. But later the Danish state punished them and thereby making them double victims of this conflict,” says Henrik Skov Kristensen, who is historian and Director at The Frøslev Camp Museum.

Nis Friedrich Jürgensen was sentenced 14 months for his activities in Zeitfreiwillig, and together with the other German sympathisers, he was interned at The Faarhus Camp, a prison first controlled by the occupation power under the name The Frøslev Camp, but after the war it was used for the suspected traitors of Denmark under the new name.

“My father felt they were very unjustly treated. The minority management had made propaganda and forced them into the war, and the majority had punished them by legislating retrospectively. For many years I wanted him to come with me to The Faarhus Camp and tell me about the time he spent there. But he simply did not want to go there,” Hinrich recalls.

It stayed like that for most of his life. Hinrich knew his father had been convicted, but it was never anything they talked about in his childhood or even most of his adult life.

Time heals all wounds

After Hinrich Jürgensen was elected President of the Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger in 2007, he was invited to a debate about the minority and the trials after 1945. Hinrich once again asked his father to come, and after 62 years, Nis Friedrich agreed. While the debaters did not agree on every aspect, the point was to lay out motivations from both sides and try to see the case from each other’s perspective.

“When we drove home, he said to me: “Now, I actually feel like I’ve gotten the apology that I have been longing for. Now, I am ready to go there.”, Hinrich recounts.

By there, Nis Friedrich meant The Faarhus Camp. Hinrich and his father drove less than 20 minutes’ drive from their home to visit the barracks where the father had been imprisoned and for the first time Hinrich got insights to the events that had impacted their and many other families’ fate. Two years later, Nis Friedrich Jürgensen passed away.

From bombing to UNESCO

German memorial sites in South Jutland were bombed most probably by Danish resistance power during the summer of 1945. The trials and convictions gave the Danes a sense of justice and historian Henrik Skov Kristensen explains it probably warded off the majority to take further actions for justice into their own hands.

“The reprisal attacks indicated how deep the contradictions were. That Danes committed these crimes is an expression of how much they were against the German Minority being present,” Skov says.

While the minority for many years considered the trials as unfair and a collective punishment, Hinrich Jürgensen believes it is one of the main reasons why there still is a German minority in South Jutland. The Faarhus prisoners shared the feeling of unjust treatment which only made the comradeship among the minority stronger in a time where many otherwise disclaimed their German heritage.

While many of the minority’s political top were imprisoned after the war, a small group of moderate German minded wrote a declaration of loyalty to the Danish state in 1945. That included an acceptance of the 1920 border. This later became the foundation of the Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger, the interest group Jürgensen is President of.

“The declaration of loyalty to the Danish state was a fundamental requirement to build a relationship in the long term. Without that I do not believe there would have been any basis for a reconciliation,” Henrik Skov Kristensen explains.

Jürgensen agrees that the declaration of loyalty was an essential step towards a friendly cooperation between the minority and majority. However, he also highlights a moral agreement between German and Denmark in 1955, where the two nations agreed to ensure human rights for the minorities on both sides as well as protect their right for cultural differences.

“Politicians today talk about the border area like there has not even been the smallest bump along the way since 1920 and that is rubbish. There have been plenty of conflicts,” says Skov.

Reflecting on the name calling at the handball court, Hinrich Jürgensen experienced as a child, the relationship has come a long way since. He says that he nowadays never – or very, very seldom – experiences stigtimazating. Earlier this spring, representatives from the German and Danish government signed the application for the relationship between Danes and Germans in the border region to be accepted on UN’s list of cultural heritage. It will be decided later this year if the relationship will be accepted on the UNESCO 2021-list.

“We feel we are accepted as a part of the society and acknowledged as adding value to the area,” and adds: “First, we were against each other. Then we were with each other. And today, we desire each other,” Hinrich concludes.